Lisa Ranford-Cartwright research paper activity

24-Sep-2011

"We're geneticists," says Dr Ranford-Cartwright. "We map genes."

In this final activity we're going to start looking at Lisa's research in a little more detail.

So far we've talked about what she does and why, with a little bit about how she does it.

So far we've talked about what she does and why, with a little bit about how she does it.

You might think that's all that can be done in school with cutting-edge research like Lisa's.

Molecular biology is highly technical and much of it isn't part of school science or even undergraduate university science. Then again research is a team effort and a single scientist rarely makes big breakthroughs on his or her own. Instead they contribute parts of the jigsaw that whole groups of people are putting together.

This too makes it hard to see the whole picture.

But that doesn't mean we can't get a grip on how Lisa does her research or what she has been finding out.

Making sense of science

Scientists report their work in scientific papers published in journals. They write these so that other scientists can understand exactly what they did and what they found out.

That means these papers can be difficult for non-scientists to read and understand.

But it is possible to get lots of information from a scientific paper, even if you're not a scientist. We're going to take a first look at how, using techniques from two different fields - language learning and journalism. You've already met some of these techniques in earlier Real Science activities, in the Basic Lesson Plans and in the discussion and research activities.

Journalists often write about things they know little about when

they first take on an assignment. But what they write still needs to make

sense and be backed up by knowledge and understanding. They often get

sent huge technical reports, which can be as hard to follow as

scientific papers.

Journalists often write about things they know little about when

they first take on an assignment. But what they write still needs to make

sense and be backed up by knowledge and understanding. They often get

sent huge technical reports, which can be as hard to follow as

scientific papers.

The secret is to learn the essentials fast, ask the right questions and relate what you learn to what you already know. And never read every word.

DARTs and linguistics

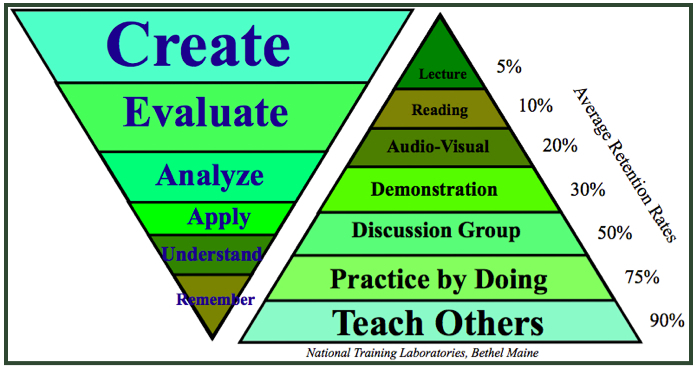

Two sources of valuable techniques in tackling new science belong broadly to the field of applied linguistics. They are directed activities related to text - DARTs for short - and reciprocal reading, the foundation of the basic lessons plans we provide for each science story.

The basic idea in both is to make reading interactive, interesting and easier to understand. So a lot more of what we read will stay in our memory.

The linguistic analysis of science research stories, such as Lisa's, into different statement types, which we did in the basic lesson plans, is a form of directed activity related to text. We're going to build on that here.

Statements about science

research, as we've seen, can be placed in one of a dozen

categories. Here they are again

1. New finding or development – what's new?

2. Accepted knowledge – what's old?

3. Methods or technology – how they did it

4. Possible application – what we can use it for

5. Aims of the research or reasons for doing it

6. Hypothesis

7. Evidence

8. Prediction

9. Future work

10. Question

11. Issue, analogy, speculation, scenario, point for discussion

12. Personal or other non-science statements

So how does this help us in tackling a piece of scientific writing we know nothing about? Well it gives us the hooks we need to hang it on. It takes us a big step along the road to understanding the science.

And it helps us ask the right questions to get the gaps in our knowledge filled.

Statement category activity

Let's have a go.

In your groups try classifying the statements in this short story from Science Daily about tackling the malaria parasite.

Use coloured pencils, numbers, letters, notes in the margin or any other method that appeals to you. Here's the article in a Word file you can work with.

Use coloured pencils, numbers, letters, notes in the margin or any other method that appeals to you. Here's the article in a Word file you can work with.

Although it might not seem so, this is a much harder piece of writing for young learners than our news story about Lisa.

The reason is the level of language used in it. If we run it

through Word's built-in readability checker we find it has a Flesch

Reading Ease of  14.5 and a Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level of 12.0. Using

this online readability tool it comes out even worse, with a Flesch-Kincaid grade level of 15.8 and a Gunning Fog index of 18.6.

14.5 and a Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level of 12.0. Using

this online readability tool it comes out even worse, with a Flesch-Kincaid grade level of 15.8 and a Gunning Fog index of 18.6.

What this means is that this story is pretty unreadable for the vast majority of young learners whether they understand the science or not..

The statement-categorising DARTS exercise helps us get to grips with the content. Have a go and then take a look at what we thought.

This is not necessarily a better answer than yours. There are bound to be disagreements. Telling the difference between a new finding for instance and a hypothesis can be hard, sometimes - even for the scientists doing the research.

But talking about a disagreement like that, and figuring out which kind of statement it is and why, is very useful in understanding how science works. Differences of opinion should be seen as opportunities for discussion, not errors to be corrected.

Scientific paper

So now let's use these methods to take a first look at one of Lisa's published papers.

It's called "Plasmodium Falciparum  Accompanied the Human Expansion out of Africa ". Have a quick scan through this

paper and share your first impressions with your group and with your

teacher. Write a few of these comments down and keep them for later.

Accompanied the Human Expansion out of Africa ". Have a quick scan through this

paper and share your first impressions with your group and with your

teacher. Write a few of these comments down and keep them for later.

We are now going to get over a few of the barriers to our understanding of this paper

First there are the words. Let's take a look at the Summary to the paper, which we've taken out and put into our Real Science format.

In a scientific paper such as this, a large number of the words can be unfamiliar, which seems to make understanding impossible. But let's take things a step at a time.

First we provide pop-definitions for a fair number of the hard words. These should help get the first glimmerings of meaning from the text. At the foot of the story we also provide pop-up meanings for hard words used in the pop-up meanings in the text.

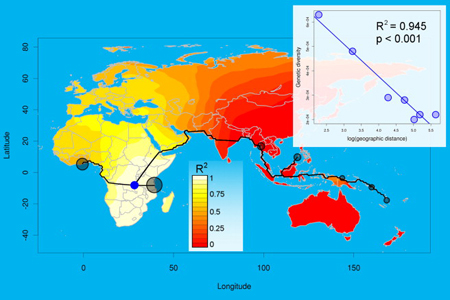

The following, for example, becomes a bit easier to follow when you know what negative correlation, genetic diversity, geographic and sub-Saharan mean:

"We observe a strong negative correlation between within-population genetic diversity and geographic distance from sub-Saharan Africa"

Questions from categories

We're going to add a new element now, which we can do because Lisa has agreed to take part in this project.

We're going to add a new element now, which we can do because Lisa has agreed to take part in this project.

In your groups you're going to put together questions, as you did for your colleagues with reciprocal reading. But this time it's questions that will help us understand the research behind the scientific paper - questions for Lisa.

Once we've got all your questions we're going to get Lisa to answer them, through a video link or in person.

So how do we get good questions to put to a scientist about a paper she has written that we only dimly understand? We start by asking questions of the text ourselves, using our statement categories.

First a question about questions.

How do we know that a sentence is a question? In writing it's easy because there's one of these ? at the end of the sentence. In speech you can often tell by the way the words are spoken. You usually hear a rising tone in a person's voice at the end of a question.

But we often know that it's a question just from the first word. Why? How?

That's right. There are a set of words that signal that what follows is a question. Why and How are two of them. We also have Who, What, When and Where.

So let's try matching these to our Categories. Suppose we want to find out more about Methods and Technology. Which word is our question most likely to start with? (How?)

Have a go at completing the following table, using one or more of the question words (pupil activity): Who, What, When, Where, Why, How.

| Kind of statement | Question word |

| New finding | What? |

| Methods and technology | How? |

| Aims of the research | Why? |

| Possible application | How? Why? |

| Accepted knowledge | Who? What? Where? |

There's another useful tip to help generate questions. For each kind of statement you should look first at the kind of words in it shown in the following table:

| Kind of statement | Good words to look at |

| New finding | Nouns and phrases |

| Methods and technology | Verbs |

| Aims of the research | Verbs |

| Possible application | Verbs |

| Accepted knowledge | Nouns and phrases |

Questions for Lisa

So let's use these tables to help generate questions about Lisa's science from the summary.  First we want to know what kind of statements are in that summary.

First we want to know what kind of statements are in that summary.

So let's have a go. Using coloured pencils or the shadings provided in the Categories Word file, classify as many of the statements in the Summary as you can.

Here are our thoughts. As always, differences are points for discussion.

Now let's look at what we've got - and think about what we don't have. We seem to have the following statements in the summary:

1. New finding or development

2. Accepted knowledge

3. Methods or technology

5. Aims of the research or reasons for doing it

But we don't seem to have any statements about:

4. Possible application – what we can use it for.

Nor do we seem to have any of these:

6. Hypothesis

7. Evidence

8. Prediction

9. Future work

10. Question

11. Issue, analogy, speculation, scenario, point for discussion

12. Personal or other non-science statements

But hang on a minute. There are statements in the summary we haven't classified

yet, because they don't fit into one of the five most common categories. Here they are:

1. ... and point to a joint sub-Saharan African origin between the parasite and its host.

2. Age estimates for the expansion of P. falciparum further support

3. ... that anatomically modern humans were infected prior to their exit out of Africa and carried the parasite along during their colonization of the world.

What kind of statement do you think these are?

I'd say that 1 is a hypothesis, 2 is evidence for a hypothesis and 3 is another hypothesis, similar to 1, and saying a little more about it.

So we might want to make this Question 1 for Lisa:

"Are we right that 1 is a hypothesis and so is 3? Or does the work described in this paper mean that both of these are more than "tentative explanations"? Have you more or less proved they are true?"

What next? Well we can work through the main categories, looking at the statements we've got on each and thinking up questions we want answered.

Methods statements

Here's the methods statement from the summary:

"Here we analyze a worldwide sample of 519 P. falciparum isolates sequenced for two housekeeping genes (63 single nucleotide polymorphisms from around 5000 nucleotides per isolate)."

The pop-ups tell us a little more about this, but it's still not easy to understand. Let's ask Lisa. But because we've got a little information now, we don't just say, "Tell us how you did the research."

We're pretty sure we wouldn't understand the answer to that, right off.

Instead we look at what we have, and ask her to expand and explain. We break the sentence down and, when we're dealing with methods and technology, we focus on the verbs - and we start with How questions.

So for "we analyze a worldwide sample", we might ask Lisa how they analyzed the sample and how they got the sample in the first place.

So for "we analyze a worldwide sample", we might ask Lisa how they analyzed the sample and how they got the sample in the first place.

We could also ask what they mean by a sample. We know it means "a small amount used to tell what a whole thing is like". But what does that mean in this case? What's the small amount? How do you get it?

Do we have any other verbs in our sentence on methods? Well "sequence" is a verb and it's used in the phrase "sequenced for two housekeeping genes". So we could ask "Did you do the sequencing? Was this part of the analyzing you talk about or was it the next step? How did you do the sequencing?"

New findings

Questions arising naturally from new findings statements are of several different types. You might ask a How question - such as how exactly did you find that out? But notice that you're asking about Methods and technology, not about the new finding itself.

In the same way if you ask how the new finding might be useful, you're asking about Applications.

There's no reason why you shouldn't ask these type of questions here. But it's useful to be clear in your own mind what type of question you are asking.

Questions about the new finding itself that aren't about Methods or Applications are usually about making sure we understand what the statement means - what it is the researchers actually found out - or at what the new finding told the researchers, and what it suggested they should do next, and why.

So let's take a look at the new findings statements in this summary. There is just one and here it is:

" We observe a strong negative correlation between

within-population genetic diversity and geographic distance from

sub-Saharan Africa (R2 = 0.95) over Africa, Asia, and Oceania."

Nouns and phrases include "negative correlation", "within-population genetic diversity" and "geographic distance from sub-Saharan Africa".

We have some feel for what this means, because we know what each of the words means separately. We want Lisa to help us put them together into something that makes sense.

We know that negative correlation is "a relation between two sets of numbers such that when one is high the other is low, and vice versa".

So that tells us that when "geographic distance from sub-Saharan Africa" is high, then "within-population genetic diversity" is low.

What does that tell us? What does it mean? What is the hypothesis - the tentative explanation - for this new finding?

Applications

One fairly important tip on generating questions for scientists. Please don't start with possible applications of the research, unless there are a lot of application statements in the paper you're looking at - which in this case there aren't.

Scientists get questions about applications of their research all the time, from journalists and other people who don't understand the science. They do understand about applications, so that's what they usually get the scientists to talk about.

Which can get very boring for the scientists.

What they want to talk about is what we know and don't know, what they think might be the explanation, what they're trying to do and how, what they've found out so far and what they are planning to do next. (existing knowledge, aims, hypotheses, methods, new findings, evidence, future work).

So whatever other questions you come up with for Lisa, leave this one for last:

"We've noticed that your summary doesn't talk directly about possible applications of the research in this paper. Are there any? How can your research be applied in the real world? Why would you want to do that?"

Last thoughts on categories and questions

Remember, to really understand a scientist's work, you want to know all of the following about it :

What are the aims of the research?

What are the new findings or developments?

What's the accepted knowledge we need to understand what's going on?

What methods or technology did the scientist use?

What are the possible applications of this research?

If we can get answers to the first set of questions we also have a second set. They are:

What hypothesis were you testing?

Did that generate a prediction?

What evidence did you find for or against your hypothesis?

What questions are still unanswered?

What future work do you want to do in this area?

What issues or points for discussion does this work raise?

You might also want to ask the scientist personal or non-science questions - which they might answer.

Further reading

1) DARTS in Times Educational Supplement Scotland 2) Directed activities related to text in primary school science. 3) Seeing through texts: developing discourse-based materials in teacher education. 4) Skimming and scanning

How to read a scientific paper: 1) University of Arizona, 2) School of Natural Science, Hampshire College, 3) Clayton State University